There’s been a rich conversation unfolding recently that I wanted to draw your attention to, because of its pertinence to Slow Church.

In the face of fragmenting modern culture, Rod Dreher wrote a compelling piece almost a year ago on “The Benedict Option”:

Should [Christians] take what might be called the “Benedict Option”: communal withdrawal from the mainstream, for the sake of sheltering one’s faith and family from corrosive modernity and cultivating a more traditional way of life?

More recently Samuel Goldman has offered a different option, that of the biblical prophet Jeremiah, which I take to be based more on Jeremiah’s advice to Ancient Israel in exile than on Jeremiah’s experience as a prophet:

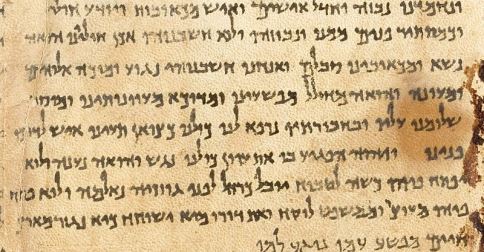

Thus saith the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel, unto all that are carried away captives, whom I have caused to be carried away from Jerusalem unto Babylon; build ye houses, and dwell in them; and plant gardens, and eat the fruit of them; take ye wives, and beget sons and daughters; and take wives for your sons, and give your daughters to husbands, that they may bear sons and daughters; that ye may be increased there, and not diminished. And seek the peace of the city whither I have caused you to be carried away captives, and pray unto the Lord for it: for in the peace thereof shall ye have peace. (Jeremiah 29:4-7)

Dreher responded the next day with a comparison of the two options, which he summarized:

It is becoming clear that in our time, if you are not consciously and vigorously countercultural in your Judaism, modernity is going to flatten you — not by persecution, but by inculcating lassitude and indifference. Same deal with Christianity. As Flannery O’Connor said:

“Push back against the age as hard as it pushes against you. What people don’t realize is how much religion costs. They think faith is a big electric blanket, when of course it is the cross.”

“The cross,” meaning more broadly (and ecumenically), real sacrifice.

This is why I think the Benedict Option is a more reasonable response to the conditions under which traditional Jews and Christians live today than Goldman’s Jeremiah Option, even though the two share a lot in common. Both address general strategies through which moral and religious traditionalists try to live in a broader culture that is more or less hostile to their beliefs and commitments. Both have the same goal: maintaining the integrity of the tradition and the vitality of the community in a condition of exile. The relatively open, relaxed Jeremiah Option makes more sense if the community has a fairly robust identity and internal cohesiveness that is not seriously threatened by the outside. The more defensive and rigid Benedict Option makes more sense if the community faces a more serious threat to its identity and internal cohesiveness.

All three of these reflections are worth our careful reading and reflection. (Please do follow the above links and read the full articles).

I have argued on this blog for a variation of the Benedict option (Macintyre did, after all, suspect that the new Benedict would be “doubtless very different”) in which culture was preserved not through marginalized and radical faith communities, but through ordinary church communities, which I suppose begins to sound more like Jeremiah than Benedict.

In addition to drawing your attention to this conversation, I also wanted to recommend a resource that will be helpful in shedding some new light on these conversations, Phil Kenneson’s little book Beyond Sectarianism, (in the excellent Christian Mission and Modern Culture Series). Kenneson not only challenges us to consider what is meant by the — usually pejorative — term “sectarian,” are we setting ourselves apart from the world, the rest of the church, or both? Benedict, in reacting to the then relatively recent convergence of church and empire in Constantine, offered a way of life that was an alternative to both church and world. Believing that we can exist apart from the whole of God’s people poses a serious threat to the fundamental unity of the Body of Christ. Kenneson also reminds us that the distinction between church and world is primarily about the narratives and convictions we live by:

Christians should regard the world not as a separate place, but as a way of life ordered by a set of narratives, practices, and convictions that is at odds with the narratives, practices and convictions that the church is called to embody as a condition of its discipleship to Jesus Christ. … What distinguishes communities of Christians from the world is that they respond to all of life by embedding the fragmented and competing narratives of the world within the narrative of God’s dealings with creation through Israel, Jesus Christ and the church. That is, all stories, practices, convictions and institutions are re-imagined from within this particular narrative framework.

…

This way of construing the relationship between church and world offers one potentially promising way of understanding and negotiating membership in multiple communities. It suggests that the peculiar identity of a given community is better grasped in narrative terms (as a group of people who share certain convictions and engage in certain practices on the basis of their orientation to a common story) than in spatial categories (as geographically separable and distinct communities). Even when such spatial categories are used only metaphorically — as when Christians are criticized for “withdrawing” from a certain cultural activity — the spatial metaphor remains misleading , because it assumes that Christians were previously located within this sphere and only later withdrew. Instead, Christians should be urged to interpret and narrate their lives as part of the ongoing narrative of the God of Jesus Christ’s interaction with God’s creation. Or perhaps more accurately, Christians should be encouraged to consider how this narrative of the ongoing work of God in Christ helps them re-imagine their participation in activities that usually offer their own narrative frameworks. If Christians participate in professional societies, trade unions, universities, political parties, nuclear families, and neighborhoods, then they will need to be sure that such participation is entered into and evaluated on the basis of of their commitment to God in Christ. In short, a Christian’s loyalty to these groups is always penultimate, being circumscribed by his or her overarching loyalty to the God revealed in Jesus Christ. It is when these institutions are regarded as autonomous (as they commonly are in the West), thereby demanding that their narratives stand independent of one another, that participation in multiple communities leads to fragmentation (87-89).

AND one final thought from Kenneson, that is pertinent to Slow Church, and our emphasis on conversation/discernment as central to our identity and mission as churches:

Living in the midst of the world as an alternative community requires the ability to function as a community of discernment. Much of this ongoing discernment will be focused on whether the community is being faithful to its call to be an embodied witness in and for the world without being of the world. Without the courage to ask difficult questions about its own life and encourage reform in light of that questioning, the church always risks becoming indistinguishable from the world. As [Nils] Block-Hoell asserts, “the real reason for religious protest is often that the church has changed and become a mirror of society instead of the salt of the earth.” (100, emphasis added)

The virtue of the Benedict Option is that is shaped around communities whose life together is shaped around an alternative narrative; the virtue of the Jeremiah Option is that it emphasizes that the community of God’s people must live in the midst of and for the world. The challenge as Kenneson describes it — and John and I would emphasize that it is one that should be undertaken slowly! — is to exercise these virtues in our ordinary church communities at the same time!

IMAGE CREDIT: Our Lady of Gethsemani Abbey. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

![Book Giveaway – Reading For the Common Good [3 copies]](http://slowchurch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/RFTCG-Cover-Banner.jpg)

Leave a Reply